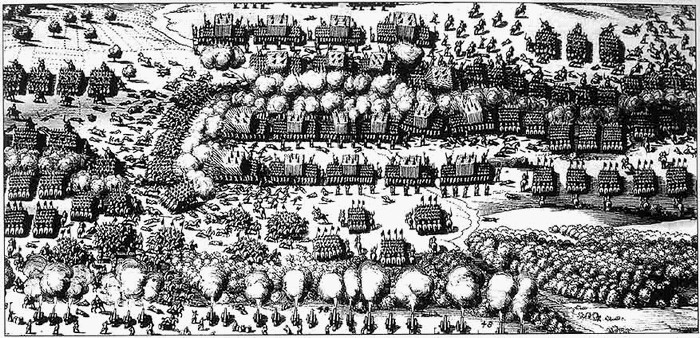

With his rear secured, Adolphus started inland picking up fresh recruits along the way. A new flurry of propaganda pamphlets were sent out, with the rudimentary Photoshop edits adding Johann Georg alongside a portrait of Gustavus Adolphus. Together their forces closed in on Tilly near the city of Leipzig. Tilly’s men had recently taken and sacked the city, and it was all the veteran Catholic could do to hold them together from all out mutiny. There was no question of retreating to friendly territory nor really of fleeing deeper into Saxony. The two options facing Tilly were either hole up in Leipzig and wait for reinforcements, or march out and crush his enemies. Ultimately the choice was made for him by his more impetuous second in command Gottfried Heinrich Pappenheim, and after reporting a short skirmish near Leipzig the rest of Tilly’s forces were called in. The battle hardened imperial army turned to face the Saxon and Swedish forces on September 17th, 1631 at a place known to history as Breitenfeld.[1]

Gustavus Adolphus was an innovator in some ways, but perhaps it’s better to say he simply understood how to utilize what was already there. In the 17th Century each gunsmith used their own compounds, and each produced gun was a work of art with little standardization. As a result many of the inventions that came to dominate later wars like breach loading or match lock muskets were already conceived, they just weren’t practical without widespread adoption and refinement. The same held true for artillery, which was divided between “light” and “heavy” pieces based on the size of the shot, neither of which were truly mobile and used a wide array of calibers and designs. Adolphus would take both elements and sharpen them to a killing point in his army.

Adolphus’ engineers first put a leather sheathed iron cannon with a three pound iron ball to use, then later a four pound bronze cannon that loaded faster and had longer range. Even better, a rudimentary wooden casing was rigged around the ball to create the first artillery shell. Unlike his contemporaries these smaller pieces could be hauled and served by three men, and it gave his army the power to bring down the thunder of artillery at will. The best available muskets and tactics were also brought to bear in the Swedish army. Combined with thinner, smaller units of cavalry and infantry drilled to work in concert with the cannon, and Adolphus had the most flexible army of the war. This creative thinking was born out of necessity, as much as anything. Sweden and Finland simply lacked the kind of manpower reserve to compete against the Empire or Spain without an extra three pound hunk of iron packed into their punch. But the results would speak for themselves. More than anyone before Napoleon, Adolphus defined the gunpowder era of warfare, and study of his tactics and battles continues to this day.

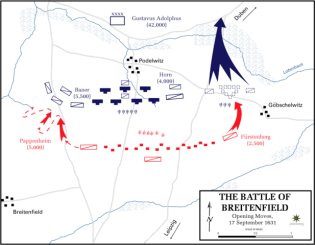

As Breitenfeld was a meeting encounter, both sides took the ample time necessary to deploy properly. Adolphus took his own right flank, with his trusted General Horn in the middle, and the Saxon forces under Johann Georg on the left. Even at the time the allies made for a study in contrasts. Johann Georg’s green Saxon troops were resplendent in their new uniforms which Adolphus termed, “a cheerful and beautiful company to see”.[2] The Swedes, Finns, and Scots of Adolphus were much more heterogeneous in appearance. So much so that they had actually taken to cutting branches and inserting them in their helmets to identify friendly units. Adolphus himself was unarmored except for a leather buff coat, owing to an old musket wound the armor rubbed against.[3]

Tilly’s own trusted general Pappenheim took the left opposite Adolphus, and his other general Fürstenburg sat across from the Saxons. Tilly in the middle commanded the 17 blocks of Spanish style Tercios, highly coordinated units of 2,000 pikes and musketeers apiece. On paper the battle must have seemed even. While Tilly was slightly outnumbered at 35,000 to 42,000, his men had been fighting for years and he was well acquainted with his officers. His first moves confirmed this thought as well, and after an early artillery duel a massed cavalry charge led by Fürstenburg slammed hard into the Saxons on the left wing.

Through the first charge the Saxons held, but already shaken by the artillery barrage when a wave of light Croatian horsemen screamed down at them for a second time the entire line buckled and fled. No one could claim the dishonor of flight quite as much as Elector Johann Georg himself, who made it a good fifteen kilometers before even stopping to check pursuit. As added insult to injury, the routing Saxon cavalry paused just long enough to sack their Swedish ally’s baggage train. At first glance the whole thing must have seemed confusing due to the gunpowder smoke, but likely just another Imperial triumph.

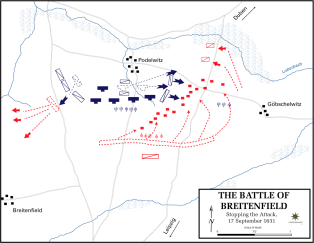

Yet on the other flank, things were going sour fast for Tilly. For hours Pappenheim’s cavalry had been circling the Swedish flank, but every time his men wheeled into range they had been met by a massed volley of fire by the Swedes. Frustrated, Pappenheim had tried to ride around the entire Swedish line, only to find himself face to face with the reserve units, armed and waiting for him. In general the Swedes’ formations baffled the Imperials. Their squares were thin mixtures of infantry and cavalry, rather than 2,000 man juggernauts. There seemed to be no blind spots to their guns, and their rate of fire was three times that of their imperial counterparts. After a few hours of this Pappenheim’s men were exhausted and badly depleted.

Even stranger, rather than break like most armies would, the Swedes had deployed their reserves at a right angle to cover the exposed flank and kept right on fighting. Distracted by the chance to sack the Saxon camp, Fürstenburg’s recircling cavalry attack was halfhearted and easy to throw off. Behind the reformed Swedish line, the artillery kicked into high gear, ripping holes in the tightly packed imperial center as it advanced. Half again outnumbered by his enemies, Adolphus barely seemed to notice. He was everywhere at once on the field, howling encouragement to his men in the teeth of the battle. At around 4PM the Swedish right thundered out and crashed into Pappenheim’s exhausted troops and kept right on going into the imperial artillery line.

Before Tilly fully understood his situation, he was flanked by combined force of cavalry and infantry which was already turning his own captured guns on the Catholic pike men. Tilly himself was wounded twice in the resulting rout, as the only major imperial army in the field disintegrated by nightfall. Of the 35,000 Tilly had brought to the field, 7,000 still marched to his drumbeat by the end of his retreat a little over a week later.

Breitenfeld was a massive chink in the aura of imperial success. For many Catholics it had been easy to say that God had been on their side for years. Even in the Prague Defenestration their agents had stuck the landing with the grace of God on their side. Breitenfeld shattered that impression, and panic in the Catholic ranks followed close on its heels. In Bavaria Maximilian abruptly dropped his opposition to Wallenstein as he realized that French assurances for his security meant little to the rapidly approaching Swedes. Back off the benches once again, Wallenstein began to rearm as the war entered its most violent phase.

[1] German for “Wide Field”. German is a beautifully functional and at times aggressively literal language.

[2] Wedgwood 2005

[3] This is called foreshadowing.